Where do I start?

It can be a little intimidating to create an online writing class either from the ground up or to try and convert your face-to-face writing class to an online writing class. Even if you have a lot of support from a WPA or you've used a lot of digital technology in your normal face-to-face classes, the task of creating an online writing course can still be daunting.

There are so many things to think about when designing an online writing course. Some of these things will be second nature and others might be new challenges. We've collected a few basic suggestions (building off on our own experience) and listed them below.

The length of courses can have an impact in how you design your writing assignments. Whether it is a 6 week course, a 10 week course, or a 16 week course, the goals for each are the same. The difficult task is trying to achieve those goals in less than half the time of some of the longer courses. Some common misconceptions we run into with students who sign up for online writing courses is that they will be easy and not require as much work. The truth is, this is not the case. It requires even more time and effort for both the teacher and student, but in the end, the reward will be worth it.

There are a couple of scenarios that can exist for your beginning your online writing class. Here are a few that we have identified and have tailored this site to help:

Whatever scenario you fall under, this site is here to help. There are probably more scenarios, and even if that is the case, we still made this site for you! We want you to know that this site is here to help you build an online writing class, get ideas for your current online writing class, and serve as a space for you to find great research, current articles, submit and share ideas, and provide a supporting online community for you and your students to succeed.

We've begun by sharing some of our own course materials, but with time, we're hoping that all of you visiting this site will help contribute to our collection, and we encourage you to submit by visiting the Connect page on this site.

There are so many things to think about when designing an online writing course. Some of these things will be second nature and others might be new challenges. We've collected a few basic suggestions (building off on our own experience) and listed them below.

The length of courses can have an impact in how you design your writing assignments. Whether it is a 6 week course, a 10 week course, or a 16 week course, the goals for each are the same. The difficult task is trying to achieve those goals in less than half the time of some of the longer courses. Some common misconceptions we run into with students who sign up for online writing courses is that they will be easy and not require as much work. The truth is, this is not the case. It requires even more time and effort for both the teacher and student, but in the end, the reward will be worth it.

There are a couple of scenarios that can exist for your beginning your online writing class. Here are a few that we have identified and have tailored this site to help:

- I have been given an online writing class and I have no idea what to do and I have no WPA or help from my department.

- I have been given an online writing class and I have no idea what to do, but I have help from my WPA and department, but neither has OWI experience.

- I have been given an online writing class, but I have taught online before and I am looking for new ideas.

Whatever scenario you fall under, this site is here to help. There are probably more scenarios, and even if that is the case, we still made this site for you! We want you to know that this site is here to help you build an online writing class, get ideas for your current online writing class, and serve as a space for you to find great research, current articles, submit and share ideas, and provide a supporting online community for you and your students to succeed.

We've begun by sharing some of our own course materials, but with time, we're hoping that all of you visiting this site will help contribute to our collection, and we encourage you to submit by visiting the Connect page on this site.

Break up the Content

|

Creating modules or learning tasks is a really important component of a successful online writing course because it allows students to understand how their knowledge builds upon earlier knowledge as they begin to understand that they are developing their skills over the course. The best way to make modules is to start with the larger writing assignments, then break them out into several different tasks.

Modules can be anywhere from 2 weeks to 6 weeks depending on the amount of content involved during the module. In a 16 week course, you could have two four week modules and 2 three week modules. In a 6 week course, you might only have three two week modules. Creating a module around a writing assignment is not a difficult task. For example, if the students are being asked to write a research paper, have them pick a topic in a discussion forum one week, then have them do research and submit an annotated bibliography. Follow those activities up with a brainstorming assignment, an outline or rough draft, and then have them submit the final research paper as the last task in that module. You have a limited amount of time with a lot of content to cover in a way that still meets the goals and outcomes of your class and program. By being Strategic and breaking up the content into a manageable timeline, you allow yourself to be Available and Responsive. For further reading on "chunking" or "modules" check out chapter two "Design with the Future in Mind" in Robin Smith's book Conquering the Content and chapter two "Course Lessons and Content: Translating Teaching Styles to the OWCourse" in Scott Warnock's book Teaching Writing Online: How & Why. |

Start by Making a Clear Path in the CMS

|

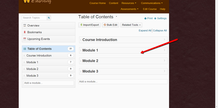

When designing the layout of your course it is really important to be Strategic. Clarity in the design navigation is also an extension of being Available to students. Not only do instructors want to be available, but the material/content should be available (usable) to the students. Being Strategic in the use of images or videos on the course home page or other areas in the class also helps make the class more Personal.

One tip to keep in mind is to keep the navigation minimal: the less places to go the better! Here are two examples from two different classrooms (each uses a different CMS) to illustrate keeping the content navigation simple. For an extended discussion on clarity and minimal design, check out Jessie Borgman's article, "Clarity in an Online Course as an Extension of Onsite Practice" in The OWI Open Resource journal. For further reading on designing a clear path in the CMS, check out Norman Coombs book Making Online Teaching Accessible: Inclusive Course Design for Students with Disabilities. |

Don't Forget you are Human

|

Here is a revised version of a talk that Jessie Borgman gave at CCCCs 2014. This presentation focuses on why it's important for students to see the instructor as a human being and how an instructor can present him/herself in this way to his/her students. This presentation is a very clear example of the PARS philosophy of online writing instruction shared here on this page. It explains how instructors can be Personal, Available, and Responsive to their online students while also being Strategic in their course design and delivery.

This example gives some ideas of how instructors can actually interact and show their human side in their online writing classrooms. Along with the .pdf here on the left, here are two supporting documents that go with this presentation that further illustrate how to be yourself (human) with online students: Connectedness Example and Student Communication. For more discussion on developing your online writing instructor personality, check out chapter one, "Getting Started: Developing Your Online Personality" in Scott Warnock's book Teaching Writing Online: How & Why. |

Video Conferencing & Collaboration

In our face-to-face classes we are Strategic in when we schedule conferences. This gives us a chance to see where students are at and if they need any help or support. The same can be accomplished online via video conferencing. A simple ten minute video conference can serve as a better collaborative interaction between you and your student than a long email that merely repeats what you have already said in the assignment sheet or in the syllabus. By allowing yourself to be seen and heard you make the class more Personal, your make yourself more Available, and to be far more efficient and effective Responsive instructor.

However, you will find that many students who sign up for online classes do not have the time to meet face-to-face and thus, written communication might be the only way for them to respond. Students also may feel uncomfortable meeting with their instructor online, and thus, it is important to respect the time and social preferences of your students by not forcing the issue. Most video conferencing applications will allow for audio only, there are chat applications that can be used, and even writing in shared documents are excellent places to work with students if they would prefer not to communicate via video. Casey McArdle utilizes video conferences often with is online writing courses and says "whatever impediment I have encountered with students concerning video conferencing, we have always found a way to create a synchronous space where we can work together to answer any questions or concern." For more ideas on how the instructor can build a community and help prepare students for the challenges of online writing courses, check out chapter thirteen, "Preparing Students for OWI" in Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction by Heidi Harris and Lisa Meloncon and Beth Hewett's book The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors.

However, you will find that many students who sign up for online classes do not have the time to meet face-to-face and thus, written communication might be the only way for them to respond. Students also may feel uncomfortable meeting with their instructor online, and thus, it is important to respect the time and social preferences of your students by not forcing the issue. Most video conferencing applications will allow for audio only, there are chat applications that can be used, and even writing in shared documents are excellent places to work with students if they would prefer not to communicate via video. Casey McArdle utilizes video conferences often with is online writing courses and says "whatever impediment I have encountered with students concerning video conferencing, we have always found a way to create a synchronous space where we can work together to answer any questions or concern." For more ideas on how the instructor can build a community and help prepare students for the challenges of online writing courses, check out chapter thirteen, "Preparing Students for OWI" in Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction by Heidi Harris and Lisa Meloncon and Beth Hewett's book The Online Writing Conference: A Guide for Teachers and Tutors.

Other Ways to Utilize Video and Audio

Currently, the NCTE sponsored OWI Open Resource journal features several pieces that focus on tools and best practices (tied specifically to OWI Principles), which can be used in the OWC. Jason Snart’s piece “Welcome Announcements in the LMS” provides an excellent example of the importance and effectiveness of the use of sound in the OWC. Snart indicates, “This practice allows me to be more present for my online students so they can see and hear me. Because many instructors and students affectively feel a distance in asynchronous courses particularly, seeing my face and hearing my voice can remind them that I am human, aware of them as people, and generally there for them.” Snart’s argument of reminding students that he is human is a great example of the effectiveness of video and sound in OWI because it acknowledges that the online environment is isolating in and of itself; however, bringing human elements into the OWC is possible, even if instructors have to work harder to bring human elements into the class. For more on welcome videos and course orientation videos, see Jason Dockter’s piece, “Improve Access with a Course Orientation.”

Jodi Whitehurst’s text “Screencast Feedback for Clear and Effective Revisions of High-stakes Process Assignments” exemplifies how video can be used to help students improve their writing skills. Whitehurst states that “By creating screencast videos for feedback, online writing faculty are able to indicate specific needs for revision within student assignments, discuss possible approaches for revising, display assignment rubrics to specify criteria that are and are not being met, direct writers to online resources, and give “voiced” affirmations to developing writers.” Whitehurst’s use of sound shows how using voice and video feedback on assignments can help students feel like their instructor is involved in helping them become better writers; it can also contextualize instructor comments on their assignments. In a sense, this feedback mimics traditional f2f office hours, giving students a video that can be played back multiple times and allow them to view it and write up a series of questions or comments that they can then send back to their instructors. Further, since the software used has a free version (Jing), students and instructors could create an ongoing conversation of shared videos; instructor responds to student writing assignment, student responds to instructor comments/feedback all through video.

Jodi Whitehurst’s text “Screencast Feedback for Clear and Effective Revisions of High-stakes Process Assignments” exemplifies how video can be used to help students improve their writing skills. Whitehurst states that “By creating screencast videos for feedback, online writing faculty are able to indicate specific needs for revision within student assignments, discuss possible approaches for revising, display assignment rubrics to specify criteria that are and are not being met, direct writers to online resources, and give “voiced” affirmations to developing writers.” Whitehurst’s use of sound shows how using voice and video feedback on assignments can help students feel like their instructor is involved in helping them become better writers; it can also contextualize instructor comments on their assignments. In a sense, this feedback mimics traditional f2f office hours, giving students a video that can be played back multiple times and allow them to view it and write up a series of questions or comments that they can then send back to their instructors. Further, since the software used has a free version (Jing), students and instructors could create an ongoing conversation of shared videos; instructor responds to student writing assignment, student responds to instructor comments/feedback all through video.